In this article

AES

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) is one of the most widely used encryption algorithms in the world. Its origins date back to the late 1990s when the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) launched a public call to find a symmetric encryption algorithm to replace the already obsolete DES (Data Encryption Standard). This process was a response to the growing need to strengthen security in data transmission in an increasingly complex digital environment.

Timeline of the Selection Process

-

1997: NIST issues a call for proposals for algorithms that could be candidates to become the new encryption standard.

-

August 1998: A total of 15 encryption algorithm proposals are received, some of which came from prominent researchers and cryptographers around the world.

-

August 1999: After an exhaustive evaluation and analysis process, 5 finalist algorithms are selected. These algorithms were assessed for their security, efficiency, and performance.

-

October 2, 2000: Finally, the algorithm known as Rijndael was chosen as the new AES. This algorithm, developed by Belgian cryptographers Vincent Rijmen and Joan Daemen, stood out for its simplicity and robustness against potential cryptographic attacks.

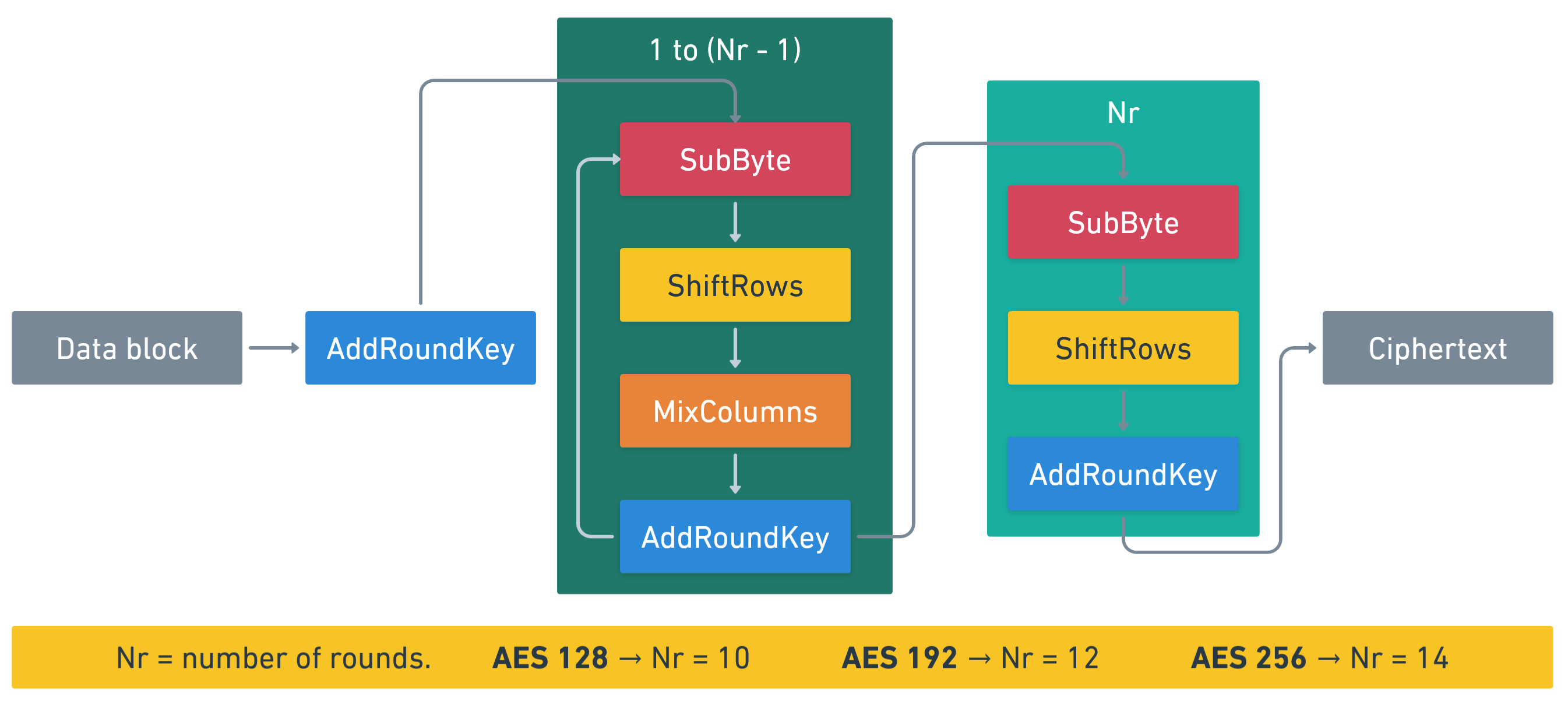

When encrypting data, AES divides it into blocks of 128 bits (16 bytes) and encrypts them through several rounds. Each 16-byte block is referred to as “state.” The number of rounds varies depending on the key length used in the algorithm:

AES 128 -> 10 rounds

AES 192 -> 12 rounds

AES 256 -> 14 rounds

In AES, 4 phases can be distinguished:

- SubByte

- ShiftRows

- MixColumns

- AddRoundKey

The algorithm begins with the AddRoundKey phase using the unchanged encryption key.

Then, for all rounds except the last, it will perform the 4 stages we have seen earlier.

For the last round, it will go through all phases except for MixColumns.

Let’s take a closer look at what these phases consist of.

1. SubByte

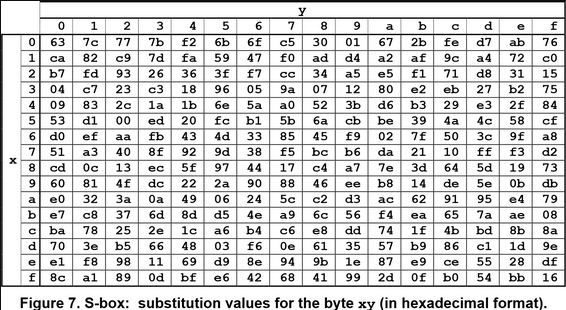

This stage introduces confusion into the encryption process. In this phase, byte substitutions are performed using the S-box table. This table is a pre-established substitution matrix of 256 values, where each possible value (if represented in hexadecimal, it would be the values ranging from 00 to FF) corresponds to a byte in that table. Let’s look at an example.

We have the hexadecimal value:

Ai = f5

If we look at the image below, we can see that ‘x’ represents the rows of the S-box table, while ‘y’ represents the columns.

Source: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/FIPS/NIST.FIPS.197.pdf

Source: https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/FIPS/NIST.FIPS.197.pdf

Following that rule:

x = f

y = 5

If ‘x = f’, then we will obtain a value from the last row, the one with the letter ‘f’. And if ‘y = 5’, our substituted value will be in row ‘f’ column ‘5’, which is ‘e6’, and we will represent it as ‘Bi’.

Ai = f5 -> S-box -> e6 = Bi

Calculation of the S-box Table

But how are the values of this table calculated? To obtain each value:

- The multiplicative inverse is calculated in GF(2^8).

- An affine function is applied.

GF(2^8) is the Galois field that has 256 elements (2^8 = 256). A very superficial definition of a ‘field’ can be this: a set of elements where you can add, subtract, multiply, and divide (where all elements except 0 have a multiplicative inverse). In GF(2^8), each element is a polynomial of degree at most 7 (x^7), and Galois fields of base 2 (GF(2)) can only have coefficients of 0 or 1. I think we will understand it better with an example.

Let’s return to our hexadecimal byte:

Ai = f5

The binary representation of ‘f5’ would be:

f = 1111

5 = 0101

That is:

Ai = 1111 0101

Although it may not seem like it, because we said that the elements of GF(2^8) are polynomials, this number is an element within the field GF(2^8):

Ai = 1111 0101 = 1x^7 + 1x^6 + 1x^5 + 1x^4 + 0x^3 + 1x^2 + 0x + 1 = x^7 + x^6 + x^5 + x^4 + x^2 + 1

Bits = 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Powers = 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

Ai(x) = x^7 + x^6 + x^5 + x^4 + x^2 + 1

We could say, intuitively, that each power represents the position of a bit within a byte (8 bits).

Calculation of the Multiplicative Inverse

After understanding this, we can move on to what the inverse of a number is. Given a number ‘a’, its inverse ‘a^(-1)’ is the one that, when multiplied by ‘a’, gives us the result ‘1’:

a · a^(-1) = 1

We want to obtain the inverse of Ai(x):

Ai(x) · Ai(x)^(-1) = 1.

The value o Ai(x)^(-1), if ‘Ai(x) = x^7 + x^6 + x^5 + x^4 + x^2 + 1’, is:

Polynomial: x^6 + x^2 + x

Bits: 0100 0110

Hexadecimal: 46

Here are all the multiplicative inverses for each possible value:

| 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|--|

0 |-- 01 8d f6 cb 52 7b d1 e8 4f 29 c0 b0 e1 e5 c7

1 |74 b4 aa 4b 99 2b 60 5f 58 3f fd cc ff 40 ee b2

2 |3a 6e 5a f1 55 4d a8 c9 c1 0a 98 15 30 44 a2 c2

3 |2c 45 92 6c f3 39 66 42 f2 35 20 6f 77 bb 59 19

4 |1d fe 37 67 2d 31 f5 69 a7 64 ab 13 54 25 e9 09

5 |ed 5c 05 ca 4c 24 87 bf 18 3e 22 f0 51 ec 61 17

6 |16 5e af d3 49 a6 36 43 f4 47 91 df 33 93 21 3b

7 |79 b7 97 85 10 b5 ba 3c b6 70 d0 06 a1 fa 81 82

8 |83 7e 7f 80 96 73 be 56 9b 9e 95 d9 f7 02 b9 a4

9 |de 6a 32 6d d8 8a 84 72 2a 14 9f 88 f9 dc 89 9a

a |fb 7c 2e c3 8f b8 65 48 26 c8 12 4a ce e7 d2 62

b |0c e0 1f ef 11 75 78 71 a5 8e 76 3d bd bc 86 57

c |0b 28 2f a3 da d4 e4 0f a9 27 53 04 1b fc ac e6

d |7a 07 ae 63 c5 db e2 ea 94 8b c4 d5 9d f8 90 6b

e |b1 0d d6 eb c6 0e cf ad 08 4e d7 e3 5d 50 1e b3

f |5b 23 38 34 68 46 03 8c dd 9c 7d a0 cd 1a 41 1c

Source: https://samiam.org/galois.html

Application of the Affine Function

Once the inverse has been calculated, an affine function must be applied to break the linearity. This process consists of multiplying a fixed 8x8 matrix (M) by the bit representation of the recently calculated inverse (Ai(x)^(-1)), followed by the addition of a constant byte (C):

Bi = M · Ai^(-1) + C

[ 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 ] [ 0 ] [ 0 ]

[ 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 ] [ 1 ] [ 1 ]

[ 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 ] [ 0 ] [ 1 ]

Bi = [ 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 ] · [ 0 ] + [ 0 ]

[ 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 ] [ 0 ] [ 0 ]

[ 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 ] [ 1 ] [ 0 ]

[ 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 ] [ 1 ] [ 1 ]

[ 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 ] [ 0 ] [ 1 ]

Source: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/5122/512253718012/html/

We need to explain that in GF(2^8), additions are performed as an XOR function, where comparing two values will yield true only if one of them is true and the other is false. When talking about bits, ‘0’ will represent the false value (False), while ‘1’ will represent true (True):

AND | OR | XOR

-----------------------------------

1 + 1 = 1 | 1 + 1 = 1 | 1 + 1 = 0

1 + 0 = 0 | 1 + 0 = 1 | 1 + 0 = 1

0 + 1 = 0 | 0 + 1 = 1 | 0 + 1 = 1

0 + 0 = 0 | 0 + 0 = 0 | 0 + 0 = 0

That is, if the byte that results after the multiplication M · Ai(x)^(-1) (which we will call ‘z’) is added to C, we will obtain:

Bi = M · Ai^(-1) + C

z = M · Ai^(-1)

Bi = z + C

z | C | z + C | Bi

-----------------------------------

[ 1 ] [ 0 ] | [ 1 + 0 ] = [ 1 ]

[ 0 ] [ 1 ] | [ 0 + 1 ] = [ 1 ]

[ 0 ] [ 1 ] | [ 0 + 1 ] = [ 1 ]

[ 0 ] + [ 0 ] | [ 0 + 0 ] = [ 0 ]

[ 0 ] [ 0 ] | [ 0 + 0 ] = [ 0 ]

[ 1 ] [ 0 ] | [ 1 + 0 ] = [ 1 ]

[ 0 ] [ 1 ] | [ 0 + 1 ] = [ 1 ]

[ 1 ] [ 1 ] | [ 1 + 1 ] = [ 0 ]

Bi = 1110 0110 = e6

This is how the values of the S-box are obtained.

2. ShiftRows

This operation is very simple; the bytes of each row of the state (our 16-byte matrix) are rotated a certain number of positions to the left. This phase, along with the next one (MixColumns), provides diffusion to the algorithm.

Before After

[ b0 b4 b8 b12 ] -> Row 0: no change -> [ b0 b4 b8 b12 ]

[ b1 b5 b9 b13 ] -> Row 1: rotates 1 byte -> [ b5 b9 b13 b1 ]

[ b2 b6 b10 b14 ] -> Row 2: rotates 2 bytes -> [ b10 b14 b2 b6 ]

[ b3 b7 b11 b15 ] -> Row 3: rotates 3 bytes -> [ b15 b3 b7 b11 ]

3. MixColumns

In this stage, the fixed matrix shown below is multiplied by each column of the state:

[ 02 03 01 01 ] -> Row 0

[ 01 02 03 01 ] -> Row 1 = Row 0 rotated one position to the right

[ 01 01 02 03 ] -> Row 2 = Row 0 rotated two positions to the right

[ 03 01 01 02 ] -> Row 3 = Row 0 rotated three positions to the right

Where 01, 02, and 03 are values in GF(2^8):

01 = 0000 0001 -> 1

02 = 0000 0010 -> x

03 = 0000 0011 -> x + 1

For example, for the first column of the state, it would be:

[ c0 ] [ 02 03 01 01 ] [ b0 ]

[ c1 ] = [ 01 02 03 01 ] · [ b5 ]

[ c2 ] [ 01 01 02 03 ] [ b10 ]

[ c3 ] [ 03 01 01 02 ] [ b15 ]

c0 = 02·b0 + 03·b5 + 01·b10 + 01·b15

c1 = 01·b0 + 02·b5 + 03·b10 + 01·b15

c2 = 01·b0 + 01·b5 + 02·b10 + 03·b15

c3 = 03·b0 + 01·b5 + 01·b10 + 02·b15

If we multiply all the columns of the state, we will obtain a new matrix:

[ c0 c4 c8 c12 ]

[ c1 c5 c9 c13 ]

[ c2 c6 c10 c14 ]

[ c3 c7 c11 c15 ]

4. AddRoundKey

An XOR operation is performed between the state and a specific subkey for that round. This is the only part of the algorithm that directly involves the key. The subkeys are generated beforehand through the key expansion process. Let’s see how this phase would look for the text ‘Texto de ejemplo’:

text = 'Texto de ejemplo'

hexadecimal text = 546578746f20646520656a656d706c6f

original 128 bits key = 2b7e151628aed2a6abf7158809cf4f3c

[ 54 ] XOR [ 2b ] = [ 7f ]

[ 65 ] XOR [ 7e ] = [ 1b ]

[ 78 ] XOR [ 15 ] = [ 6d ]

[ 74 ] XOR [ 16 ] = [ 62 ]

[ 6f ] XOR [ 28 ] = [ 47 ]

[ 20 ] XOR [ ae ] = [ 8e ]

[ 64 ] XOR [ d2 ] = [ b6 ]

[ 65 ] XOR [ a6 ] = [ c3 ]

[ 20 ] XOR [ ab ] = [ 8b ]

[ 65 ] XOR [ f7 ] = [ 92 ]

[ 6a ] XOR [ 15 ] = [ 7f ]

[ 65 ] XOR [ 88 ] = [ ed ]

[ 6d ] XOR [ 09 ] = [ 64 ]

[ 70 ] XOR [ cf ] = [ bf ]

[ 6c ] XOR [ 4f ] = [ 23 ]

[ 6f ] XOR [ 3c ] = [ 53 ]

result = 7f1b6d62478eb6c38b927fed64bf2353

‘7f1b6d62478eb6c38b927fed64bf2353’ will be the bytes that move on to the SubByte phase (if we were in the last round, these bytes would be the fully encrypted text). In this case, by mixing the plaintext with the original key, we are in the initial round, so the next stage will be SubByte.

However, if we were in any round other than the initial one, what keys would we be using? For the remaining rounds, subkeys derived from the original key will be used, and we will see how to calculate them next.

Key Expansion

In this process, ‘Nr+1’ subkeys are created that will be used in the AddRoundKey phase, where ‘Nr’ is the number of rounds depending on the key size of AES:

AES 128 -> 10 rounds -> 11 subkeys

AES 192 -> 12 rounds -> 13 subkeys

AES 256 -> 14 rounds -> 15 subkeys

What are the steps involved in this process? Let’s see it for AES 128.

First, the original key is split into 32-bit words, totaling 4 words. For example:

original 128 bits key = 2b7e151628aed2a6abf7158809cf4f3c

Splitting into into 32-bit words:

w0 = 2b7e1516

w1 = 28aed2a6

w2 = abf71588

w3 = 09cf4f3c

If we want to obtain the next subkey, we will need to calculate 4 more words: w4, w5, w6, w7 (128 bits in total).

Depending on the index of that word, different operations will be performed.

The Index is a Multiple of 4

If the index is a multiple of 4, ‘i % 4 = 0’ (in our example, only index 4 is), the following operations will be performed:

-

RotWord: Rotate the 4 bytes of the word w[i-1] one byte to the left. In our example:

i = 4 w[i-1] = w[4 - 1] = w[3] = 09cf4f3c 09cf4f3c -> RotWord -> cf4f3c09For now, w4 is w3 with its bytes rotated one position to the left.

-

SubWord: Apply the S-Box to each byte of that result:

cf 4f 3c 09 -> Sbox -> 8a 84 eb 01 -

XOR with Rcon: XOR the previous result with the constant value Rcon[i/4]. In this case, we need to clarify all possible values for Rcon:

Hexadecimal values of Rcon for each round in AES 128: Ronda 0 -> 00000000 Ronda 1 -> 01000000 Ronda 2 -> 02000000 Ronda 3 -> 04000000 Ronda 4 -> 08000000 Ronda 5 -> 10000000 Ronda 6 -> 20000000 Ronda 7 -> 40000000 Ronda 8 -> 80000000 Ronda 9 -> 1B000000 Ronda 10 -> 36000000As we can see, the only part that can affect the word we intend to calculate is the first byte, because the rest are zeros. Therefore, only the first byte of our word will be altered. Let’s continue with our example:

i = 4 Rcon[i/4] = Rcon[4/4] = Rcon[1] Rcon[1] = 01000000 [ 8a ] XOR [ 01 ] = [ 8b ] [ 84 ] XOR [ 00 ] = [ 84 ] [ eb ] XOR [ 00 ] = [ eb ] [ 01 ] XOR [ 00 ] = [ 01 ] -

XOR con w[i-4]: XOR the word w[i-4] with the previous result:

i = 4 w[i-4] = w[4-4] = w[0] = 2b7e1516 w[i] = w[i-4] XOR w[i]' [ 2b ] XOR [ 8b ] = [ a0 ] w[0] XOR w[4] = [ 7e ] XOR [ 84 ] = [ fa ] [ 15 ] XOR [ eb ] = [ 9e ] [ 16 ] XOR [ 01 ] = [ 17 ] w[4] = a0fa9e17

After these four phases, we will have calculated the word w4: a0fa9e17

The Index is Not a Multiple of 4

When the index is not a multiple of 4 (‘i % 4 != 0’, in our example, all indices except 4), it only performs the XOR with the word w[i-4]:

i = 5

w[i] = w[i-4] XOR w[i-1]

w[5] = w[5-4] XOR w[5-1] = w[1] XOR w[4]

[ 28 ] XOR [ a0 ] = [ 88 ]

w[1] XOR w[4] = [ ae ] XOR [ fa ] = [ 54 ]

[ d2 ] XOR [ 9e ] = [ 4c ]

[ a6 ] XOR [ 17 ] = [ b1 ]

w[5] = 88544cb1

In this way, we can also calculate w6 and w7 to obtain the complete subkey for round 1. For the remaining rounds, the same process will be followed. As mentioned earlier, for the initial round, the “subkey” that will be used will be the original key.

As of the date of this article, no practical vulnerabilities have been found that compromise the security of this algorithm. For this reason, AES has established itself as the most widely used encryption standard worldwide, thanks to its robustness and efficiency in protecting sensitive data without sacrificing performance.

As technology advances and attack techniques become more sophisticated, the importance of using reliable encryption algorithms like AES becomes even more critical. The widespread adoption of this standard in applications ranging from online banking to secure communication highlights its relevance in today’s digital world.

In an environment where privacy and security are paramount, AES not only represents a technical solution but also serves as a fundamental pillar of the trust that users place in information technologies.